The genesis and significance of a project idea with a long-term vision

The Roma Mater Vinorum project, promoted by the Department of Agriculture of the Municipality of Rome in collaboration with Iter Vitis, a Cultural Route of the Council of Europe, aims to rediscover, celebrate, and promote the viticulture of the Italian capital: both in terms of the native products of the city and its geographical hinterland, and in terms of their potential to provide value in terms of identity, the environment, and tourism and the economy.

Conceived as a form of ‘historical compensation’ aimed at restoring the city’s leading role in the regional, national, and international winegrowing landscape, the project is structured within a planning vision that guides the city towards reconfiguring its image as a sustainable metropolis, becoming a hub for the diffusion of agricultural and oenological cultivation. These are closely intertwined and synergistic forms of cultivation meant to offer coherent responses both to the growing and internationalised phenomenon of ‘urban vineyards’, and to the direction of current commercial trends, which point to the recovery of native grape varieties as an effective means of countering food and wine business practices that have a low degree of territorial, cultural, and historical integrity.

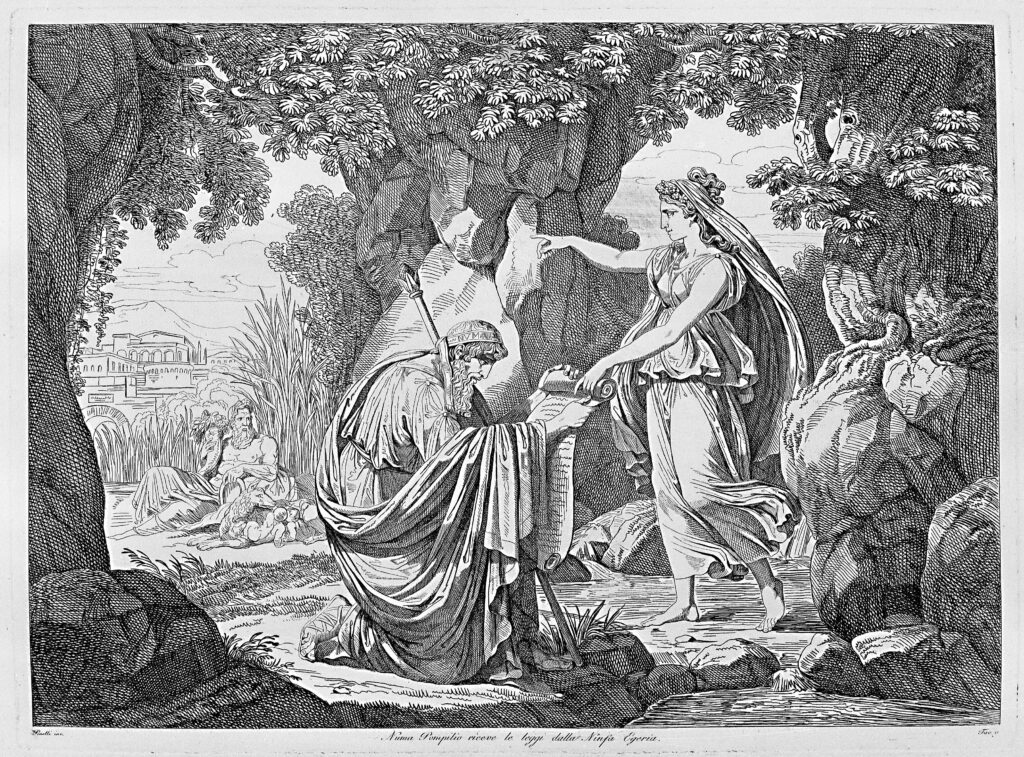

Rome and wine are linked by forms of reciprocity and mutual dependence that have existed continuously since the 8th and 7th centuries BC, when, as legend has it, King Numa Pompilius had a grapevine planted in the forum, along with an olive tree and a fig tree. Afterwards, this bond was constantly strengthened throughout the entire duration of the Empire, connected to military conquests, tying in with the right of citizenship, and intertwining with political choices and reasons of state. And while the Empire’s collapse in 476 AD marked the end of the geographical expansion of the vine, after it had taken root wherever the legions had arrived and settled, the slow effect of religion, the meticulousness of the monastic orders, and the dietary-recreational needs of medieval and modern Roman society led to Rome being filled with vast expanses of vineyards. This resulted in wine production levels that, at the end of the 16th century, were at around 20 million litres.

A truly extraordinary quantity of production that was a boon for papal taxation and that profoundly shaped the urban fabric within, and beyond, the perimeter of the Aurelian Walls. One can find direct testimony of this in the presence of Monte de Cocci – a deposit of millions of oil and wine amphorae located within the Testaccio district – the cartographic, iconographic, and photographic documentation preserved in the Capitoline archives, and the more than twenty toponymic references still testifying today to how much the vineyards were intertwined with the city’s road network, monuments, and squares – before the unification of the state and the advent of Umbertine Rome reconfigured its urban fabric and entirely stripped it of its ampelographic capital.

With such reflections as a starting point, the Roma Mater Vinorum project aims to restore the Italian capital’s role as a ‘city of wine’, reintroducing vineyards not only as practices of urban and proximity agriculture, but also as factors for the regeneration of spaces under the banner of ecology, landscape improvement, and the identity-driven reintegration of a cultural history that for millennia has unfolded sub signo vitis (under the sign of the vine).