The exemplary work of the Plaimont cooperative

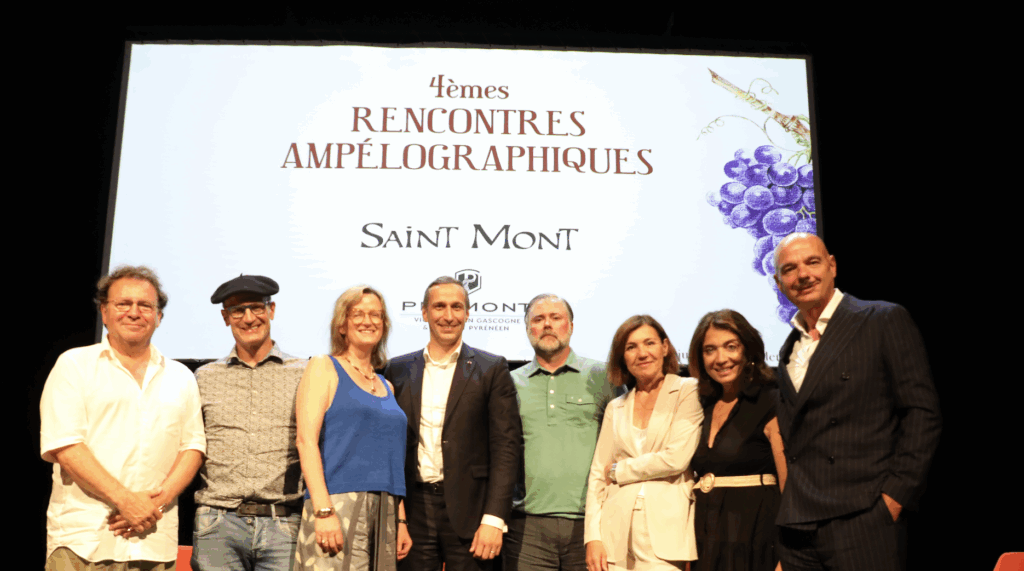

In Saint Mont, deep in the heart of Gascony’s wine country, the 4th Rencontres Ampélographiques took place on June 30 and July 1, bringing together experts, producers, and visionaries around a shared goal: rethinking the role of grapevine diversity in the future of wine. The event was hosted by Plaimont, a cooperative winery that has become a reference point in Europe for how scientific research and territorial valorisation can walk hand in hand.

Plaimont is more than a wine producer – it is a community of winegrowers bound by a vision. Over the years, the cooperative has invested time, knowledge, and resources into the preservation of viticultural biodiversity and the revival of indigenous grape varieties, treating these not as relics of the past but as strategic tools to face the future.

The event once again confirmed what many within the sector are beginning to realise: ampelography is no longer just a technical or scientific discipline – it is a strategic resource. In times of uncertainty and market fatigue, it may hold the key to reigniting public interest, reconnecting with lost consumers, and enriching the story that wine tells the world.

The two-day programme was carefully structured. The first day, held in Marciac, focused on the latest scientific developments in varietal identification, genetic conservation, and massal selection. A field visit to the parcelle patrimoine at La Madeleine and an encounter with a century-old lambrusque offered not just technical insight but a deeply emotional connection to the plant and its cultural significance. The following tasting of rare cuvées demonstrated how innovation can, paradoxically, be born from rediscovering our roots.

But it was on the second day – during the round table “Ampelography and Vine Biodiversity: How to Share This Commitment With the Wider Public?” – that the conversation turned more urgent, and perhaps more political. A core question emerged: can ampelography become a narrative engine, capable of reaching new audiences and bringing back those who have drifted away? Can it help differentiate a wine, a territory, or a wine tourism experience in an increasingly crowded and commodified market?

Xavier Thuizat, named Best Sommelier of France in 2022 and now head sommelier at Hôtel de Crillon in Paris, spoke frankly about the failures of wine communication. Too often, he said, wine speaks a language that excludes – sometimes even intimidates – and has not succeeded in welcoming consumers into the story. In this context, ampelography – with its ability to tell the life story of a vine, evoke the memory of a landscape, and express the identity of a community – could offer a more emotional, more engaging, and more accessible point of entry.

This idea was reinforced by Jeff Veir, founder of Golden Cluster in Oregon, who shared his work reviving old Sémillon clones planted in 1966 and turning them into identity pillars for a new, authenticity-driven storytelling that is resonating with younger and more curious wine lovers.

Similarly, Sarah Abbott MW, founder of The Old Vine Conference, has long argued that old vines are not just plants – they are “living heritage.” Her work draws attention to the stories encoded in these ancient vines and the urgent need to protect them, both as a source of resilience in viticulture and as cultural beacons in a rapidly changing industry.

The takeaway was clear: wine today must learn to speak again – not just about itself, but with its audience. And ampelography, far from being just a taxonomic exercise, could serve as a compelling narrative grammar. Through it, we can weave together history, archaeology, sustainability, and even diplomacy.

In an age of conflict and division, the fact that genetically identical grape varieties grow in countries currently at odds – such as Lebanon and Israel, Armenia and Azerbaijan – is a powerful reminder that the vine can unite what politics divides.

Grape varieties like Malvasia, found in countless expressions from Portugal to the Balkans, or Muscat, which links nearly all Mediterranean cultures, become symbols of a shared civilisation of taste. Ampelography, when embedded in tourism and cultural narratives, can be a strong driver of territorial attractiveness, taste education, and a more conscious form of consumption.

Several inspiring case studies were presented during the meeting. Giovanna Trisorio spoke about the Bellone al Colosseo project, which ties grape heritage to archaeological heritage in an immersive visitor experience. Gianluca Bisol recounted the rediscovery of Dorona di Venezia, a forgotten grape found by chance in an abandoned garden on the island of Torcello, now central to the Venissa project – a fusion of terroir, hospitality, and storytelling. Its recovery is not merely an agricultural success but a cultural statement.

Also discussed was the experience of the Giardino dei Vitigni Antichi by Iter Vitis in Melissa, Calabria – an open dissemination project where ampelography becomes part of school curricula and intergenerational knowledge transfer.

At a time when wine risks becoming irrelevant to younger generations and struggles to maintain market share globally, the sector has a responsibility to reinvent its communication. Not through spectacle, but through meaning. Not through jargon, but through stories.

Ampelography, in this sense, can be the new language wine needs. The Rencontres Ampélographiques of Saint Mont – and the exemplary work of the Plaimont cooperative – have issued a challenge to the sector: transform varietal knowledge into emotional, accessible, and convincing narratives. It is a challenge worth accepting.